Welcome to this week’s installment of The Scariest Part, a recurring feature in which authors, comic book writers, filmmakers, and game creators tell us what scares them in their latest works of horror, dark fantasy, dark science fiction, and suspense. (If you’d like to be featured on The Scariest Part, please review the guidelines here.)

I’m thrilled to have my good friend Helen Marshall as my guest. Her first collection, Hair Side, Flesh Side, blew me away, and her latest collection, Gifts for the One Who Comes After, looks to be just as amazing. Here is the publisher’s description:

GHOST THUMBS. MINIATURE DOGS.

ONE VERY SAD CAN OF TOMATO SOUP.

Helen Marshall’s second fiction collection offers a series of twisted surrealities that explore the legacies we pass on to our children. A son seeks to reconnect with his father through a telescope that sees into the past. A young girl discovers what lies on the other side of her mother’s bellybutton. Death’s wife prepares herself for a very special funeral.

In Gifts for the One Who Comes After, Marshall delivers seventeen tales of love and loss shot through with a profound sense of wonder. Dazzling, disturbing, and deeply moving.

And now, let’s hear what the scariest part was for Helen Marshall:

Let’s talk dead cats.

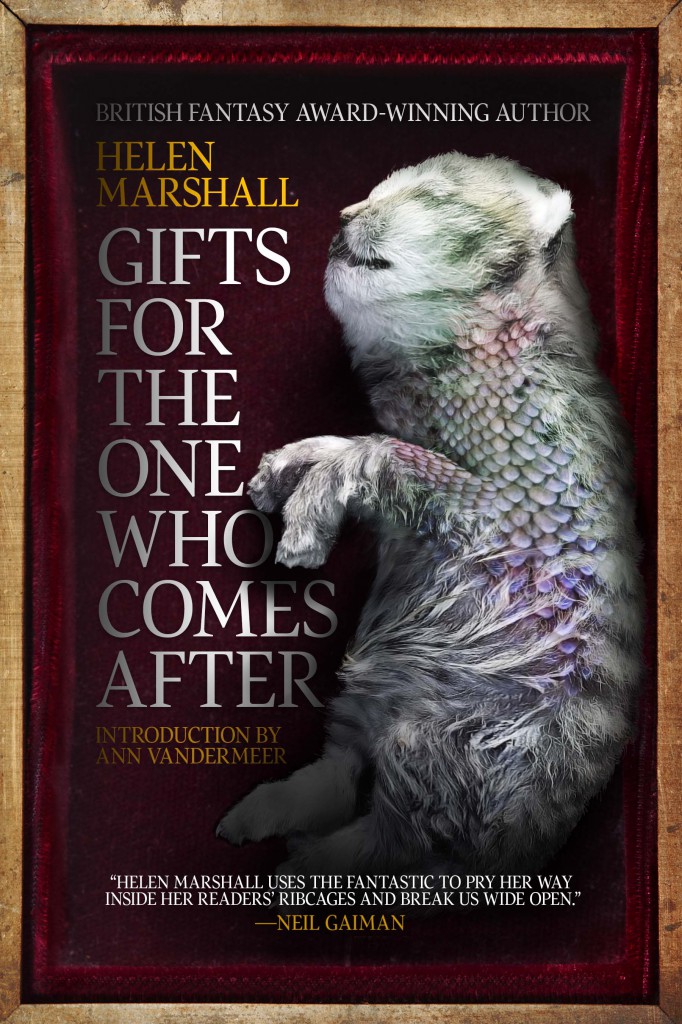

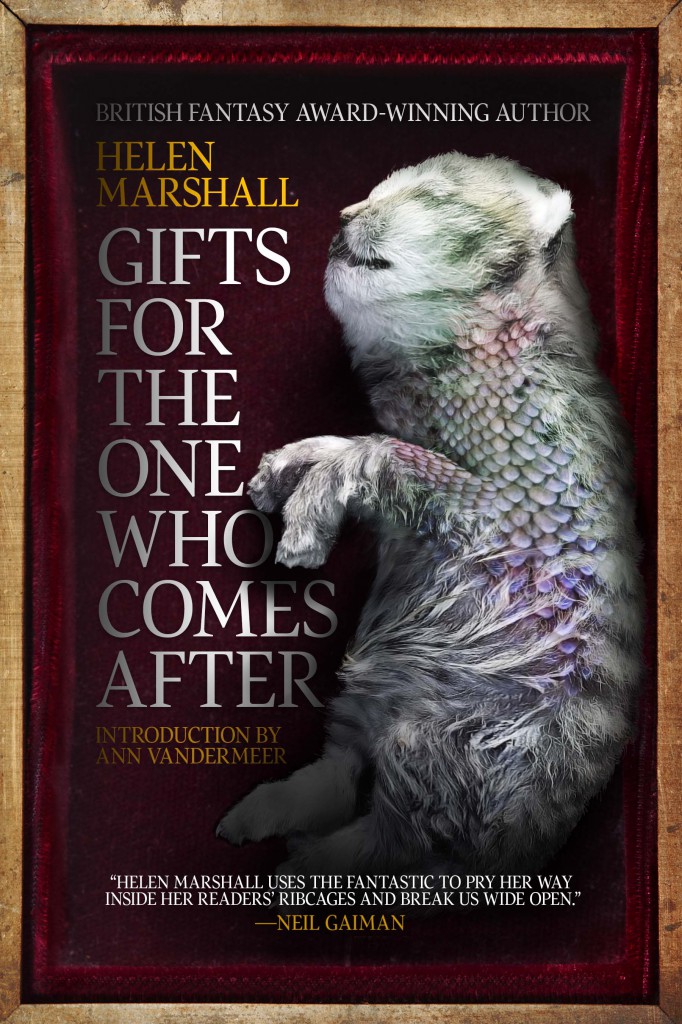

Many people’ve told me how striking they find the cover of my new collection of short stories, Gifts for the One Who Comes After — striking being translatable into anything in the range of gorgeous, sad, creepy, disturbing and downright horrifying. I’ve had people tell me they won’t buy the book because of the cover. I’ve had people tell me they have to keep the book facedown. Several reviews of the book came out used blown-up copies of my author photo rather than the book cover.

And all this really intrigues me. Because the cover doesn’t bother me in the slightest.

Here I suppose it’s worth me giving my usual disclaimer that I’m not exactly a horror writer — or I’m not a horror writer entirely — that I grew up avoiding horror movies like the plague and that it’s only in the last five years or so that I came to realize how really, seriously cool horror can be. And one of the reasons that I always feel uncomfortable saying I’m a horror writer is because my work tends to be dissonant rather than outright horrific. But what I find interesting about horror — not the genre but the emotion — is how complicated it is. Stephen King talks about three different types of emotions in this respect: terror, which is the fear of that which we cannot see or perceive fully, it is full of uncertainty and obscurity; horror, which involves actual perception of something horrid or monstrous; and revulsion, or, as he calls it, the “gag reflex” or “gross-out”.

Now this cover doesn’t look anything like a normal horror cover so it’s unclear to me what makes my cover so disturbing — except, I think, that it somehow manages to conjure up all three emotions, but none of them completely. The cover itself gives off a series of different signals to the reader. While at a glance it seems to show a dead kitten — and even I have to admit that the image of a dead kitten triggers a peculiarly specific set of sympathetic responses! — the longer you look, the less clear it becomes exactly what the creature is — the neck is too thick, the body truncated, the scales fantastic rather than horrific. The image is dissonant — it creates an uncomfortable sense that the image is at odds with itself and this, I think, is somehow more upsetting.

The cover comes out of a story called “In the Year of Omens” which Ellen Datlow bought for her anthology Fearful Symmetries. “That was the year of omens—” the story begins, “the year the coroner cut open the body of the girl who had thrown herself from the bridge, and discovered a bullfrog living in her right lung. The doctor, it was said by the people who told those sorts of stories (and there were many of them), let the girl’s mother take the thing home in her purse — its skin wet and gleaming, its eyes like glittering gallstones — and when she set it in her daughter’s bedroom it croaked out the saddest, sweetest song you ever heard in the voice of the dead girl.” This weirdly apocalyptic story follows a young girl named Leah whose family members all discover their own special omens; in fact, everyone Leah knows receives an omen — everyone except for her. The story hinges, in many respects, upon a moment when Leah comes across her baby brother’s omen: a tiny dead kitten covered with fine, translucent scales. But rather than recognizing the dead kitten as horrific, she places it for safekeeping inside a music box her father gave her. And just like the cover, the scene is somehow both horrifying and not at the same time: it’s sweet and it’s sad and it’s creepy but somehow being all of those things makes it even worse.

Horror — as a genre this time! — is interesting because despite the fact that it ostensibly feeds on a sense of the unknown, the obscured, the ambiguous, it’s also one of the most predictable and patterned genres out there. We intuitively know how a horror story is supposed to go. And that makes it, in its own weird way, both comforting and predictable. But the horror that interests me most is the horror that’s utterly unpredictable, horror that consoles even as it condemns, horror that never lets the reader know exactly what it’s up to. Because, for me, not knowing is the scariest part.

Helen Marshall: Website / Twitter

Gifts for the One Who Comes After: Amazon / Barnes & Noble / Powell’s / IndieBound

Helen Marshall is an award-winning Canadian author, editor, and doctor of medieval studies. Her debut collection of short stories, Hair Side, Flesh Side (ChiZine Publications, 2012), was named one of the top ten books of 2012 by January Magazine. It won the 2013 British Fantasy Award for Best Newcomer and was shortlisted for a 2013 Aurora Award by the Canadian Society of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Her second collection, Gifts for the One Who Comes After, was released in September, 2014. She lives in Oxford, England where she spends her time staring at old books.

![Skinjumper[1]](https://www.nicholaskaufmann.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Skinjumper1.jpg)