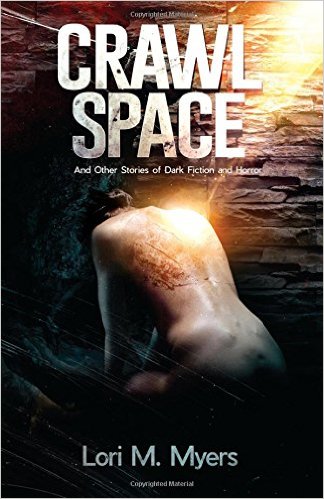

This week on The Scariest Part, my guest is author Lori M. Myers, whose new story collection is Crawlspace and Other Stories of Dark Fiction and Horror. Here is the publisher’s description:

A windowed storefront, a foreboding brothel, a wine cellar, a burial plot. Small spaces surrounded by thick walls, bolted with padlocks, weighed down with wet earth. This story collection of dark fiction/horror by award-winning writer Lori M. Myers is about the mystery and danger of closed-in rooms and wombs; of the mistaken belief that being inside equals safety. It doesn’t; not in these crawl spaces…

And now, let’s hear what the scariest part was for Lori M. Myers:

The inspiration for my story collection titled Crawlspace originated by simply reading and listening and then answering the question, “What if…?” Sometimes an idea sprang from reading an innocent new story or overhearing a conversation or by simply allowing my mind to wander during long walks. As these stories were completed and compiled, I began to notice the thread that linked them — a thread that both surprised me and yet didn’t.

So let’s rip this apart, shall we? I don’t consider myself claustrophobic by any means, but as I wrote these stories in my writing life, I noticed some revelations going on in my real life. It was in those moments (for instance, being stuck in crowded narrow hallways) that my breathing felt more constrained. I’d find myself shoulder-to-shoulder with strangers and yearned for the sea of humanity to part, to rush toward an exit door and find freedom, fresh air. I didn’t know its origins. I’d always equated indoors with safety, but the more I researched and examined the human condition, the more I realized that cramped places shut out a sometimes scary unknown if our imaginations take over.

I remember watching Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and not understanding why Vera Miles, all alone in that wretched house, got curious about a closed door leading to the basement. She was a few steps from the entrance door, a few blessed steps. Needless to say, I questioned her judgment. It appears that many other horror film characters took Vera’s lead and chose to turn the knobs of doors with ominous noises coming from the other side rather than leaving the place and phoning 911.

So I looked at my stories, asked myself what scared me, and the response was proof that having four solid walls around my fictional characters didn’t equal safety. I made bad things happen each and every time. In “Heartland Flyer,” a house serves as refuge (or is it?) from a train that kills; in “Dante’s Window,” close quarters become the “monster”; in the title story, “Crawlspace,” both the womb and the grave signify evil; in “Scar Girl,” even a Ferris wheel’s gondola becomes something other than an amusement.

Experts say that claustrophobia is an irrational fear of enclosed spaces, especially if there seems no way to escape. It could stem from our childhoods, like being left in a closet for long stretches of time or perhaps being in a crowded elevator that gets stuck between floors, neither of which happened to me. But I definitely felt it in those crowded hallways. Why?

Perhaps, when it came right down to it, it was my parents’ story that became my book’s focus and ultimately my own. Growing up, I knew little of my European parents’ experience during World War II. I knew they were Holocaust survivors, but discovered that they lived in a bunker in the Polish forest for more than three years. “Holes in the ground,” my father later told me. They would change their location often, finding another bunker to “live” in, never revealing to others in hiding exactly where their crawlspace was located for fear of being found out. That bunker became both sanctuary and a threat. A small enclosed space, yet a wrong move, a sneeze, could mean discovery, torture, death. Deep within my childlike wonder, I’d ponder what it was like for them. I’d put myself in that bunker with the monsters hovering, scouring the woods. There was no safe place in my imagination and that bunker didn’t provide one either.

We may breathe that sigh of relief as we settle in those crawlspaces, but once the door is locked and we’re inside those solid walls of wood, plaster or dirt, who knows who might be already right there, gnashing its teeth.

Lori M. Myers: Website / Facebook Group / Facebook Author Page / Twitter

Crawlspace: Amazon

Lori M. Myers is an award-winning writer of creative nonfiction, fiction, essays, and plays, a Pushcart Prize nominee, and a Broadway World Award nominee. Her works have been published in more than forty-five national and regional magazines, journals, and anthologies. Her plays and musicals have been performed internationally and across the United States and Canada. Lori is an adjunct professor of writing and literature, and senior interviews editor for Hippocampus Magazine. She holds an MA in creative writing from Wilkes University and resides in New York.