Welcome to this week’s installment of The Scariest Part, a recurring feature in which authors, comic book writers, filmmakers, and game creators tell us what scares them in their latest works of horror, dark fantasy, dark science fiction, and suspense. (If you’d like to be featured on The Scariest Part, check out the guidelines here.)

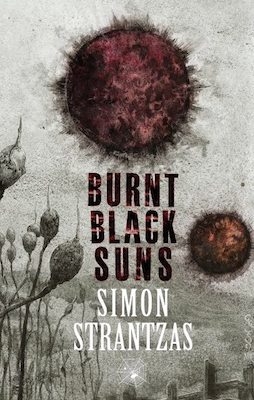

My guest is British Fantasy Award nominee Simon Strantzas, whose latest collection is Burnt Black Suns. On a personal note, I’ve known Simon for a few years now. I find him warm, funny, and incredibly smart. He was kind enough to let me stay in his guest room when I attended the World Fantasy Convention in the Toronto area in 2012, a favor that allowed me to be a part of an important convention I otherwise would not have been able to afford. I enjoy his fiction and his company very much, and I’m delighted and honored to have him as a guest on The Scariest Part. Simon already has a reputation for outstanding short horror fiction, and Burnt Black Suns is poised to bring him an even larger audience. Here’s the publisher’s description:

In this fourth collection of stories, Simon Strantzas establishes himself as one of the most dynamic figures in contemporary weird fiction. The nine stories in this volume exhibit Strantzas’s wide range in theme and subject matter, from the Lovecraftian “Thistle’s Find” to the Robert W. Chambers homage “Beyond the Banks of the River Seine.” But Strantzas’s imagination, while drawing upon the best weird fiction of the past, ventures into new territory in such works as “On Ice,” a grim novella of arctic horror; “One Last Bloom,” a grisly account of a scientific experiment gone hideously awry; and the title story, an emotionally wrenching account of terror and loss in the baked Mexican desert. With this volume, Strantzas lays claim to be discussed in the company of Caitlín R. Kiernan and Laird Barron as one of the premier weird fictionists of our time.

And now, let’s hear what the scariest part was for Simon Strantzas:

I don’t find much frightening. At least, not when it comes to fiction. The real world is plenty frightening, of course, but the world of fiction — the world of my fiction — rarely is. True, I’ve never really aimed for fright, but the nature of writing Horror means it makes its presence known whether I intended it or not. It’s a simple, indisputable fact that no matter who you are, sometimes you get frightened. But a companion truth is that everybody gets frightened by something different, so no matter how hard a writer tries, he or she can frighten no more than a fraction of readers. For me, it’s an inefficient goal to strive for. I’d rather instead focus on affecting readers’ more reliable emotions.

Burnt Black Suns was a change of pace for me, book-wise. My fiction tends to be restrained; the horrors are quiet ones, and their job (I hope!) is to seep obliquely into the reader, invading via accretion, perhaps only revealling their true nature long after reading. The slow burn is a favourite technique of mine, no question, and sometimes it takes the entire length of a story for all those little pieces to cohere into something horrific, but with Burnt Black Suns I wanted something different. I wanted to get inside you.

I suppose in some ways this was a reflection of my wanting to better exploit what might be my primary fear as a writer: lack of control over my craft. History tells me I tend to prefer short, orderly pieces. The narratives in this book, however, spin out wider and wilder than ever before, and as I wrote them I suffered the less-than-pleasant terror that I’d bitten off more than I could chew. Even the novelettes were unlike anything I’d attempted previously — both in terms of length and structure. For someone who had spent the preceeding decade writing only short stories, writing a book with four novellas was intimidating and terrifying. But also exhilarating. And enlightening.

I’m not the first writer to get lost in his own work, and I surely won’t be the last, but there were times in writing this book I didn’t know if I would ever be able to finish it, and I think that barely-contained terror informs the stories. There’s desperation there — not in the writing, but in the characters, in their reactions — a sense of spiralling out of control. My own fears infected my characters, helped to keep them off the path to safety, dragged them down into the dark. Putting together a book of short stories is so often about grabbing a handful written at a series of previous points and bundling them together. But a unified collection that is itself a journey to write can only provide its readers with a similar voyage, an equivilent transformation. At least, that’s the hope.

Burnt Black Suns is thus a triumph for me. The two novellas that together comprise half the book are different not only in style but in construction, yet still compliment each other in their outlook. Balancing them are two novelettes, one loud, one quiet, which are framed by a handful of short stories. This book, for me, was an ambitious one, and explores the full range of my weirdest work.

Writers often talk about how important it is to continue learning as time passes, and I’ve always assumed that meant no one’s prose is perfect, and that a writer must continuously sharpen and improve his or her use of language and style. Though I still believe that’s true, what I also suspect is meant is that a writer must continue to learn about him- or herself. Learn where the lines of his or her abilities are carved in stone, and where they’re drawn in dust. Where the demons are that can be called upon to dance and inform or inspire the work. Even after a quarter of my life behind the pen, I’ve learned that as terrifying as it may be to push into new realms and test myself, the results of striving for more are always worth the pain.

Simon Strantzas: Website / Facebook / Twitter

Burnt Black Suns: Amazon / Hippocampus Press

Simon Strantzas is the author of Beneath the Surface (Humdrumming, 2008), Cold to the Touch (Tartarus Press, 2009), Nightingale Songs (Dark Regions Press, 2011), and Burnt Black Suns (Hippocampus Press, 2014), as well as the editor of Shadows Edge (Gray Friar Press, 2013). His writing has appeared in The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror, The Best Horror of the Year, and The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy & Horror; has been translated into other languages; and has been nominated for the British Fantasy Award. He lives in Toronto, Canada, with his wife and an unyielding hunger for the flesh of the living.

Leave a Reply